Japanese vs Chinese Calligraphy: Key Differences in Style, Tools & Philosophy

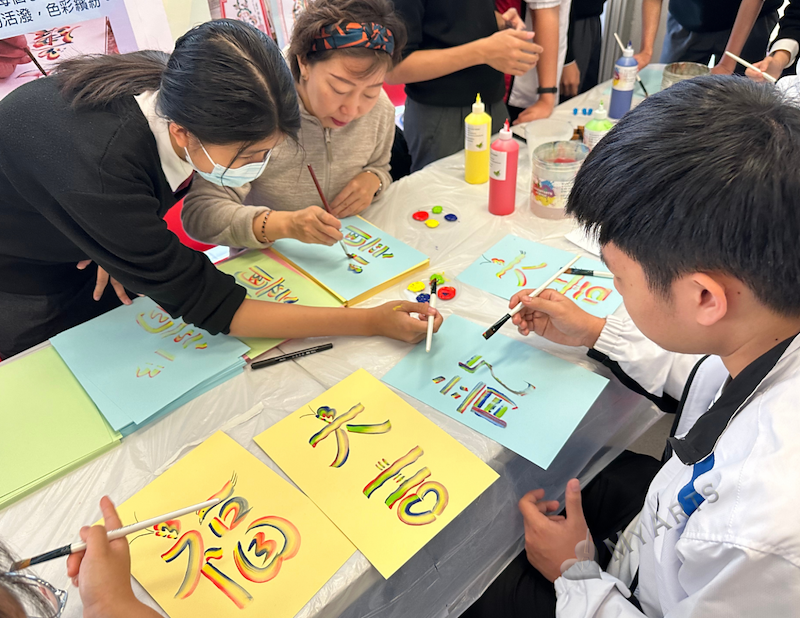

When it comes to calligraphy, a single brushstroke can carry centuries of history. Japanese and Chinese calligraphy are two of the most well-known traditions in the world, often admired for their beauty, balance, and depth of meaning. Today, you’ll even see these styles used in tattoos, art, and design—sometimes without people knowing which tradition they belong to, or what the characters actually say.

While both art forms share common roots, they evolved in different directions. Learning how to tell them apart can deepen your appreciation and help you recognize what you’re seeing at a glance. Let’s explore how Japanese and Chinese calligraphy differ in appearance, history, tools, and philosophy.

Visual Differences at a Glance

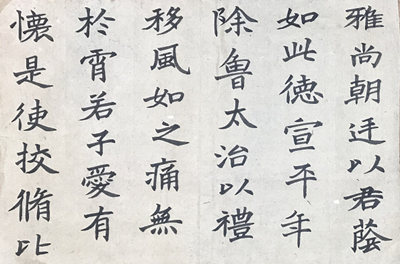

Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy, known as Shūfǎ (書法), often feels bold, expansive, and powerful. It uses only Chinese characters (hanzi) and closely follows historical stroke order and structure.

Each character is expected to stay faithful to its classical form. Precision matters deeply—deviating too far from the standard structure is often seen as incorrect rather than expressive. As a result, Chinese calligraphy tends to feel monumental and authoritative, reflecting its long imperial history.

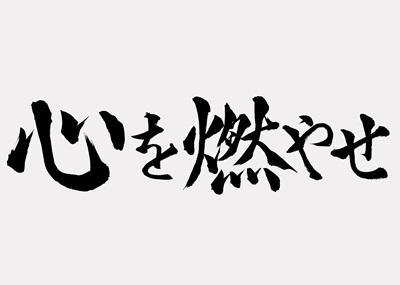

Japanese Calligraphy

Japanese calligraphy, called Shodō (書道), uses a mix of kanji (Chinese characters adapted into Japanese) and kana (hiragana and katakana). This combination gives Japanese calligraphy a softer, more rhythmic appearance.

Compared to Chinese calligraphy, Japanese styles allow more personal interpretation. Beauty, balance, and emotional expression play a larger role, and characters may be simplified or stylized for artistic effect. This flexibility gives Japanese calligraphy its quiet elegance and sense of flow.

If you’re curious how this expressive style developed, you can explore it further in our related article, The Evolution of Japanese Calligraphy, which traces how Japan shaped calligraphy into its own art form.

Origins and Historical Development

Chinese Calligraphy: The Foundation

Chinese calligraphy is one of the oldest continuous art traditions in the world, dating back over 3,000 years to inscriptions on oracle bones during the Shang Dynasty. From early on, calligraphy was tied to education, social status, and moral character.

Over centuries, multiple scripts developed—Seal Script, Clerical Script, Regular Script, Running Script, and Cursive Script—each reflecting shifts in politics, materials, and artistic taste. Mastery of calligraphy could bring prestige and influence, especially among scholars and officials.

Japanese Calligraphy: Adaptation and Innovation

Calligraphy reached Japan around the 6th century through cultural exchange with China. At first, Japanese calligraphers followed Chinese styles closely. However, because the Japanese language differs greatly from Chinese, new writing systems were created.

The development of hiragana and katakana allowed writers to better express Japanese sounds and grammar. Over time, Japan blended Chinese techniques with its own aesthetic values—simplicity, restraint, and emotional nuance—giving rise to a distinct tradition now known as Shodō.

Tools of the Trade

Shared Foundations

Both traditions rely on similar core tools:

- brush

- ink

- paper

- inkstone

In China, these are called the Four Treasures of the Study.

Chinese Calligraphy Tools

Chinese calligraphers traditionally use animal-hair brushes, ink sticks ground on inkstones, and Xuan paper, prized for its absorbency. The materials emphasize control and strength, allowing for dramatic ink variation and layered strokes.

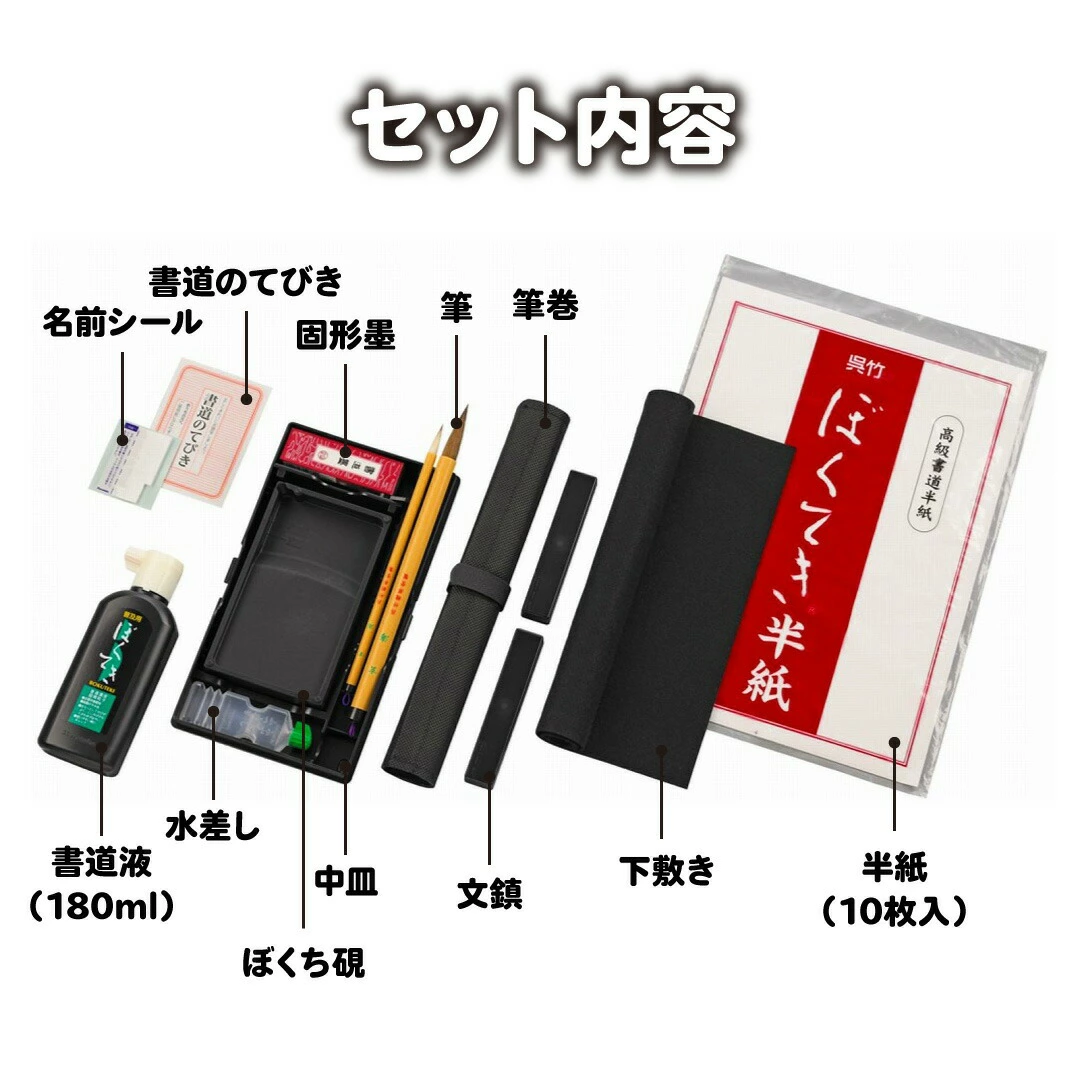

Japanese Calligraphy Tools

Japanese calligraphy uses similar tools but with local materials and names:

- Fude (brush)

- Sumi (ink)

- Suzuri (inkstone)

- Hanshi (Japanese paper speicially for shodo)

Washi paper offers a wide range of textures and absorbency levels, which supports expressive, flowing strokes. Today, many practitioners also use brush pens, making calligraphy more accessible without traditional ink preparation. These modern tools are especially popular for learning and everyday practice.

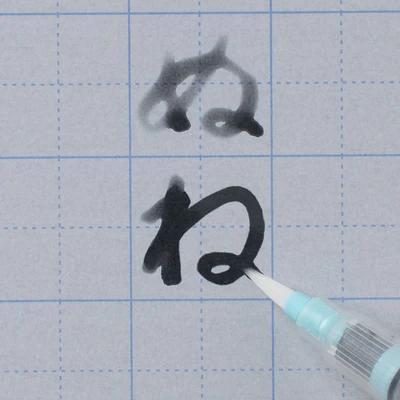

A Modern, Eco-Friendly Practice: Mizu Shodō (Water Calligraphy)

In Japan, there’s also a popular and beginner-friendly way to practice calligraphy called mizu shodō (水書道), or water calligraphy. Instead of ink, calligraphers use water and a special reusable sheet.

As you write, the water temporarily darkens the surface, clearly revealing each stroke. Once the water dries, the characters slowly disappear, leaving the sheet clean and ready to use again.

Mizu shodō is especially popular in schools, homes, and calligraphy clubs because it:

- avoids ink stains and mess

- is eco-friendly and reusable

- encourages relaxed, pressure-free practice

- allows focus on stroke order and movement rather than perfection

Because nothing is permanent, practitioners can concentrate on the flow of the brush and the feeling of each stroke. It reflects the same mindfulness found in traditional Shodō, but in a gentler, more accessible form—perfect for beginners or anyone practicing at home.

Calligraphy as a Way of Life

Chinese Perspective

In Chinese culture, calligraphy has long been associated with discipline, education, and moral refinement. The act of writing was considered a reflection of the writer’s character. Historically, only educated elites could fully engage with the art, though monks also practiced calligraphy while copying religious texts.

Because texts were copied exactly, repetition became meditative. Even today, calligraphy scrolls are displayed in homes to convey wisdom, blessings, or philosophical ideas.

Japanese Perspective

Japanese calligraphy is deeply connected to mindfulness and self-cultivation. The word Shodō literally means “the way of writing,” placing it alongside practices like tea ceremony and martial arts.

Writing is seen as a moment of focus and presence. Repeating strokes is not just practice, but a way to calm the mind. This philosophy even appears in martial arts sayings written in calligraphy, such as

剣者心也 (“Your sword mirrors your mind”), reminding practitioners that technique and mindset are inseparable.

Two Traditions, One Shared Spirit

The differences between Japanese and Chinese calligraphy go far beyond visual style. Chinese calligraphy reflects the scale and authority of a vast empire, rooted in tradition and structure. Japanese calligraphy, shaped by adaptation and aesthetic refinement, emphasizes emotion, balance, and quiet beauty.

Yet both traditions share a deep respect for the brush, the written character, and the act of writing itself.

If exploring calligraphy has sparked your curiosity, you might enjoy discovering Japanese calligraphy tools and stationery through ZenPop—whether that’s brush pens, paper, or small items that invite you to slow down and write with intention.

This article was originally written by our freelance writer Umm-Kulthum Abdulkareem and edited by us.