The Evolution of Japanese Calligraphy: History, Styles & Modern Brush Pens

If you’ve ever watched a historical Japanese or Chinese drama, you’ve probably noticed that writing wasn’t just a way to record words. It was performance, discipline, and art combined. In Japan, this art form is known as Shodō (書道), meaning “the way of writing.”

Rooted in centuries of tradition and shaped by religion, politics, and aesthetics, Japanese calligraphy has evolved alongside the country itself. While it may no longer be part of everyday life for most people, calligraphy is still taught in schools, practiced in clubs, and quietly preserved by artists and enthusiasts. Today, many people even practice Shodō using modern brush pens, making the art more accessible than ever.

Let’s take a journey through how Japanese calligraphy began, how it changed over time, and how it continues to live on today.

How Did Japanese Calligraphy Begin?

Japanese calligraphy traces its origins back to China, where writing systems and calligraphic techniques were already highly developed. Around the 6th century, Chinese characters (kanji) were introduced to Japan, along with brush writing techniques.

Early Japanese calligraphy closely followed Chinese styles, a practice known as Karayō. However, over time, Japan adapted these characters to better suit its spoken language. This led to the development of hiragana and katakana, which fundamentally changed both written Japanese and the visual style of calligraphy.

Calligraphy Through the Ages

Heian Period (794–1185): The Birth of a Japanese Style

During the Heian period, calligraphy became more expressive and personal. While scholars still copied Chinese texts, the emergence of kana scripts allowed writers to better capture Japanese pronunciation and emotion.

Hiragana, often called onna-de (“women’s hand”), became especially popular for poetry and personal writing. This softer, flowing script led to styles such as Oie-ryū, associated with the imperial court and aristocracy. Calligraphy was no longer just about accuracy. It became a reflection of sensitivity, rhythm, and refinement.

Muromachi Period (1336–1573): Calligraphy as Meditation

The Muromachi period saw the strong influence of Zen Buddhism on calligraphy. Zen monks embraced writing as a form of meditation, creating a style known as Bokuseki.

Rather than focusing on beauty or legibility, Bokuseki emphasized spontaneity and the calligrapher’s mental state. Bold, uncorrected strokes captured a single moment in time. Calligraphy became less about perfection and more about presence.

Edo Period (1603–1868): Calligraphy for the People

During the Edo period, education spread to the general population, and calligraphy became widely practiced. Calligraphy schools emerged, each developing its own approach.

New styles such as Edo moji appeared, often used for shop signs, banners, and kabuki posters. These were bold, decorative, and designed to be seen from a distance. Calligraphy expanded beyond spiritual and elite circles into everyday life and popular culture.

Meiji Period and Beyond: Tradition Meets Modern Life

The Meiji Restoration brought rapid Westernization, and traditional calligraphy faced decline as pens and printing became widespread. However, calligraphy never disappeared.

Today, Shodō is still taught in Japanese schools, practiced in clubs, and celebrated through exhibitions and seasonal competitions. Modern tools—especially brush pens—have helped bridge tradition and convenience, allowing more people to explore calligraphy without needing ink stones or animal-hair brushes.

If you’re curious about tools used today, we’ve written a dedicated guide to the best Japanese brush pens, which explores beginner-friendly options and how they compare to traditional brushes.

Major Styles of Japanese Calligraphy

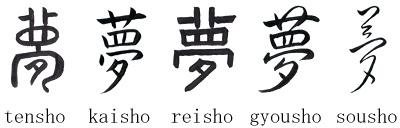

Japanese calligraphy includes several distinct styles, each with its own character:

- Kaisho (楷書) – The standard script. Clear, structured, and often the first style beginners learn.

- Tensho (篆書) – The seal script. Angular and decorative, often used for stamps and hanko.

- Reisho (隷書) – The clerical script. Wider strokes and formal balance, more legible than Tensho.

- Gyōsho (行書) – Semi-cursive. Fluid and natural, commonly used for letters and personal writing.

- Sōsho (草書) – Cursive script. Highly expressive and abstract, capturing speed and emotion.

- Bokuseki (墨跡) – Ink traces. Spontaneous and raw, rooted in Zen philosophy.

Together, these styles show how Japanese calligraphy balances discipline with freedom.

Kaisho (楷書): The Standard Script

Kaisho, the "standard script," serves as the foundation of Japanese calligraphy. This technique has squared-off strokes, emphasizing balance and uniformity. It is used for formal writing, documents, and signage; Kaisho provides a clear and structured appearance, making it readable. People start learning Shodo using the Kaisho script because it is easier than others.

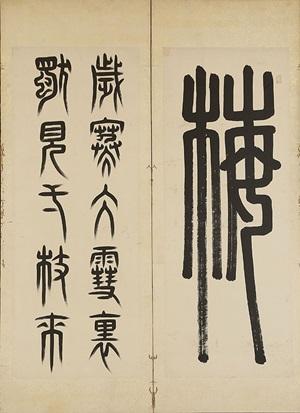

Tensho (篆書): The Seal Script

Tensho, known as the "seal script," draws its inspiration from ancient Chinese characters engraved on seals and bronze vessels. This technique has angular and geometric forms. It is used to write seals and make Hanko for document signing.

Reisho (隷書): The Clerical Script

Reisho, the "clerical script," exudes elegance and formality. This technique originated during the Han dynasty in China and later found its way into Japanese calligraphy. Reisho has smooth, flowing strokes and a balance between curved and straight lines. It was created after Tensho script because it was more legible. It looks similar to Kaisho, but it is slightly wider.

Sōsho (草書): The Cursive Script

Sōsho, the "cursive script," is the wild child of Japanese calligraphy. Here, strokes become highly abstract, flowing into one another with an almost dance-like rhythm. Sōsho is the fastest script to write, but it is difficult to read if you are unfamiliar with it. It captures the energy and spontaneity of the calligrapher's emotions.

Gyōsho (行書): The Semi-Cursive Script

Gyōsho strikes a balance between the rigid formality of Kaisho and the free-flowing nature of Sōsho. The strokes in Gyōsho are connected, so the brush seldom leaves the paper. It was derived from Reisho, and it is also called running script. This technique is commonly used in personal letters, poetry, everyday writing, and expressive pieces.

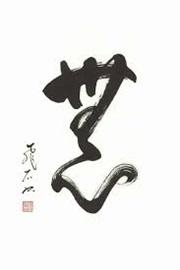

Bokuseki (墨跡): The Art of Ink Traces

Bokuseki, literally meaning "ink traces," is a technique that celebrates the unique marks left by the brush on paper. It often involves spontaneous strokes that capture the artist's state of mind. Bokuseki is less concerned with legibility and more focused on the raw, unfiltered expression of the calligrapher's emotions.

We also have a blog post talking about the Differences Between Japanese and Chinese Calligraphy, take a look if you would like to leanr more about it.

Calligraphy Today: Brushes, Brush Pens, and Everyday Practice

While traditional brushes are still used by professionals, many modern practitioners prefer brush pens. These pens mimic the feel of a brush but are easier to control, portable, and beginner-friendly.

Brush pens are now used for:

- practicing kanji

- learning calligraphy styles

- expressive lettering

- illustration and manga inking

- writing formal messages, such as names or short phrases on gift or money envelopes

You may be interested in our Best Japanese Calligraphy Pens guide if you would like to look into the Calligraphy tools for nowdays.

If you’re interested in trying calligraphy yourself, you can find a curated selection of Japanese brush pens at the ZenPop store, alongside paper and other tools suited for lettering and practice.

Japanese calligraphy is more than beautiful characters on paper. It’s a living tradition that reflects history, belief, and everyday life. Whether practiced with a traditional brush or a modern pen, each stroke carries intention.

If this journey sparked your curiosity, where will you explore next—learning a script, choosing your first brush pen, or simply slowing down to enjoy the act of writing?